1 Text analysis

In this chapter, I introduce the topic of text analysis and provide the context needed to understand how it fits in a larger universe of science and the ever-ubiquitous methods of data science. Approaches to language analysis, including methodological approaches and the nature of data, are discussed. I then introduce text analysis as a branch of data science and discuss its aims, approaches, implementation, and applications.

1.1 Enter science

The world around us is full of countless actions and interactions. As individuals, we experience this world, gaining knowledge and building heuristic understanding of how it works. Our minds process countless sensory inputs, which enable skills and abilities that we often take for granted, such as predicting what will happen if someone is about to knock a wine glass off a table and onto a concrete floor. Even if we have never encountered this specific situation before, our minds somehow instinctively make an effort to warn the potential glass-breaker before it is too late.

You may have attributed this predictive knowledge to ‘common sense’. Despite its commonality, it is an incredible display of the brain’s capacity to monitor the environment, make connections, and store information without consciously informing us about its processes.

Our brains are efficient but not infallible. They do not store every experience in raw form; we don’t have access to records like a computer would. Instead, our brains excel in making associations and predictions that help us navigate the complex world we inhabit. In addition, our brains are prone to biases that can influence our understanding of the world. For example, confirmation bias leads us to seek out information that confirms our beliefs, while the availability heuristic causes us to overestimate the likelihood of easily recalled events.

Our brains are doing some amazing work, but that work can give us the impression that we understand the world better and in more detail than we actually do. In this way, what we think the world is like and what the world is actually like can be two different things. This is problematic for making sense of the world in an objective way. This is where science comes in.

Science starts with a question, identifies and collects data, carefully selected slices of the complex world, submits this data to analysis through clearly defined and reproducible procedures, and reports the results for others to evaluate. This process is repeated, modifying, and manipulating the procedures, asking new questions and positing new explanations, all in an effort to make inroads to bring the complex into tangible view.

In essence what science does is attempt to subvert our inherent limitations by drawing on carefully and purposefully collected samples of observable experience and letting the analysis of these observations speak, even if it goes against our intuitions (those powerful but sometime spurious heuristics that our brains use to make sense of the world).

1.2 Data analysis

Emergence of data science

This science I’ve described is the one you are likely quite familiar with and, if you are like me, this description of science conjures visions of white coats, labs, and petri dishes. While science’s foundation still stands strong in the 21st century, a series of intellectual and technological events mid-20th century set in motion changes that have changed aspects about how science is done, not why it is done. We could call this Science 2.0, but let’s use the more popularized term data science.

The recognized beginnings of data science are attributed to work in the “Statistics and Data Analysis Research” department at Bell Labs during the 1960s. Although primarily conceptual and theoretic at the time, a framework for quantitative data analysis took shape that would anticipate what would come: sizable datasets which would “[…] require advanced statistical and computational techniques […] and the software to implement them.” (Chambers, 2020) This framework emphasized both the inference-based research of traditional science, but also embraced exploratory research and recognized the need to address practical considerations that would arise when working with and deriving insight from an abundance of machine-readable data.

Fast-forward to the 21st century, a world in which machine-readable data is truly in abundance. With increased computing power, the emergence of the internet, and the wide adoption of mobile devices, electronic communication skyrocketed around the globe. To put this in perspective, in 2019 it was estimated that every minute 511 thousand tweets were posted, 18.1 million text messages were sent, and 188 million emails were sent (“Data never sleeps 7.0,” 2019). The data flood has not been limited to language, there are more sensors and recording devices than ever before which capture evermore swaths of the world we live in (Desjardins, 2019).

Where increased computing power gave rise to the influx of data, it is also one of the primary methods for gathering, preparing, transforming, analyzing, and communicating insight derived from this data (Donoho, 2017). The vision laid out in the 1960s at Bell Labs had come to fruition.

Data science toolbelt

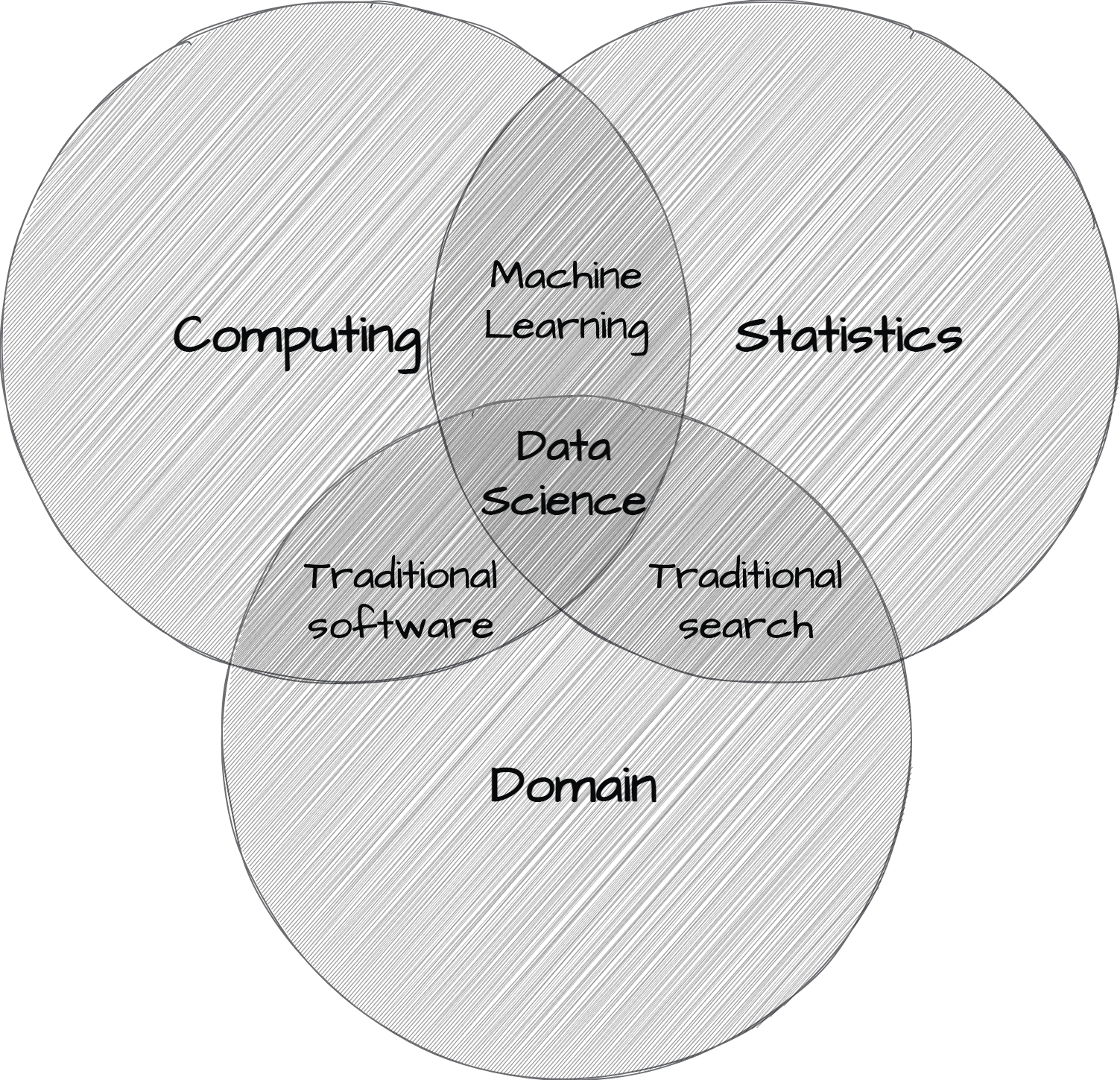

Data science is not predicated on data alone. Turning data into insight takes computing skills, statistical knowledge, and domain expertise. This triad has been popularly represented as a Venn diagram such as in Figure 1.1.

The computing skills component of data science is the ability to write code to perform the data analysis process. This is the primary approach for working with data at scale. The statistical knowledge component of data science is the ability to apply statistical methods to data to derive insight by bringing patterns and relationships in the data into view. Domain expertise provides researchers insight at key junctures in the development of a research project and aids researchers in evaluating results.

This triad of skills in combination with reproducible research practices is the foundational toolbelt of data science (Hicks & Peng, 2019). Reproducible research entails the use of computational tools to automate the process of data analysis. This automation is achieved by writing code that can be executed to replicate the data analysis. This code can then be shared through code sharing repositories, where it can be viewed, downloaded, and executed by others. This adds transparency to the process and allows others to build on previous work enhacing scientific progress along the way (Baker, 2016).

Quant everywhere

Equipped with the data science toolbelt, the interest in deriving insight from data is now almost ubiquitous. The science of data has now reached deep into all aspects of life where making sense of the world is sought. Predicting whether a loan applicant will get a loan (Bao, Lianju, & Yue, 2019), whether a lump is cancerous (Saxena & Gyanchandani, 2020), what films to recommend based on your previous viewing history (Gomez-Uribe & Hunt, 2015), what players a sports team should sign (Lewis, 2004), now all incorporate a common set of data analysis tools.

The data science toolbelt also underlies well-known public-facing language applications. From the language-capable chat applications, plagiarism detection software, machine translation algorithms, and search engines, tangible results of quantitative approaches to language are becoming standard fixtures in our lives.

The spread of quantitative data analysis too has taken root in academia. Even in areas that on first blush don’t appear readily approachable in a quantitative manner, such as fields in the social sciences and humanities, data science is making important and sometimes disciplinary changes to the way that academic research is conducted.

This textbook focuses in on a domain that cuts across many of these fields; namely language. At this point let’s turn to quantitative approaches to language analysis as we work closer to contextualizing text analysis in the field of linguistics.

1.3 Language analysis

Qualities and quantities

Language is a defining characteristic of our species. Since antiquity, language has attracted interest across disciplines and schools of thought. In the early 20th century, the development of the rigorous approach to study of language as a field in its own right took root (Campbell, 2001), yet a plurality of theoretical views and methodological approaches remained. Contemporary linguistics bares this complex history and even today, it is far from a theoretically and methodologically unified discipline.

Either based on the tenets of theoretical frameworks and/or the objects of study of particular fields, methodological approaches to language research vary. On the one hand, some language research commonly applies qualitative assessment of language structure and/or use. Qualitative approaches describe and account for characteristics, or “qualities”, that can be observed, but not measured (e.g. introspective methods, ethnographic methods, etc.)

On the other hand, other language research programs employ quantitative research methods either out of necessity given the object of study (phonetics, psycholinguistics, etc.) or based on theoretical principles (cognitive linguistics, connectionism, etc.). Quantitative approaches involve “quantities” of properties that can be observed and measured (e.g. frequency of use, reaction time, etc.).

These latter research areas and theoretical paradigms employ methods that share much of the common data analysis toolbox described in the previous section. In effect, this establishes a common methodological language between other language-based research fields but also with research outside of linguistics.

The nature of data

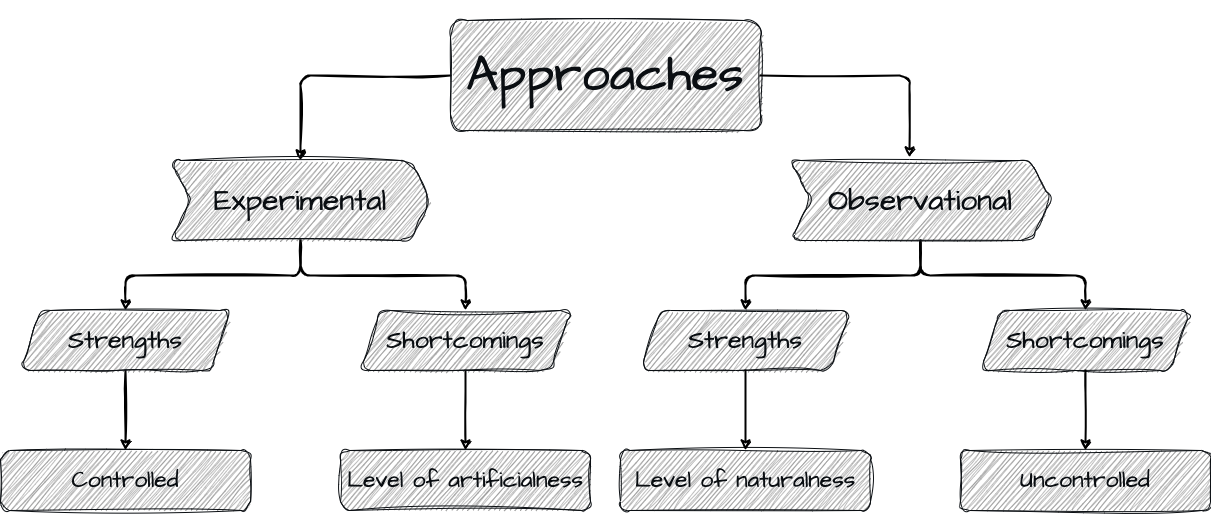

In quantitative language analysis, there is a key methodological distinction between experimental and observational data, which affects both procedure and interpretation of research.

Experimental approaches start with an intentionally designed hypothesis and lay out a research methodology with appropriate instruments and a plan to collect data that shows promise for shedding light on the likelihood of the hypothesis. Experimental approaches are conducted under controlled contexts, usually a lab environment, in which participants are recruited to perform a task with stimuli that have been carefully curated by researchers to elicit some aspect of language behavior of interest. Experimental approaches to language research are heavily influenced by procedures adapted from psychology.

Observational approaches are a bit more of a mixed bag in terms of the rationale for the study; they may either start with a testable hypothesis or in other cases may start with a more open-ended research question to explore. But a more fundamental distinction between the two approaches is drawn in the amount of control the researcher exerts on the contexts and conditions in which the language behavior data to be collected is produced. Observational approaches seek out records of language behavior that is produced by language speakers for communicative purposes in natural(-istic) contexts. This may take place in labs (language development, language disorders, etc.), but more often than not, language is collected from sources where speakers are performing language as part of their daily lives —whether that be posting on social media, speaking on the telephone, making political speeches, writing class essays, reporting the latest news for a newspaper, or crafting the next novel destined to be a New York Times best-seller.

The data acquired from either of these approaches have their trade-offs. The directness and level of control of experimental approaches has the benefit of allowing researchers to precisely track how particular experimental conditions effect language behavior. As these conditions are an explicit part of the design, the resulting language behavior can be more precisely attributed to the experimental manipulation.

The primary shortcoming of experimental approaches is that there is a level of artificialness to this directness and control. Whether it is the language materials used in the task, the task itself, or the fact that the procedure takes place under supervision the language behavior elicited can diverge quite significantly from language behavior performed in natural communicative settings.

Observational approaches show complementary strengths and shortcomings, visualized in Figure 1.2. Whereas experimental approaches may diverge from natural language use, observational approaches strive to identify and collected language behavior data in natural, uncontrolled, and unmonitored contexts. This has the benefit of providing a more ecologically valid representation of language behavior.

However, the contexts in which natural language communication take place are complex relative to experimental contexts. Language collected from natural contexts are nested within the complex workings of a complex world and as such inevitably include a host of factors and conditions which can prove challenging to disentangle from the language phenomenon of interest but must be addressed in order to draw reliable associations and conclusions.

The upshot, then, is two-fold: (1) data collection methods matter for research design and interpretation and (2) there is no single best approach to data collection, each have their strengths and shortcomings.

Ideally, a robust science of language will include insight from both experimental and observational approaches (Gilquin & Gries, 2009). And evermore there is greater appreciation for the complementary nature of experimental and observational approaches and a growing body of research which highlights this recognition.

1.4 Text analysis

In a nutshell, text analysis is the process of leveraging the data science toolbelt to derive insight from textual data collected via observational methods. In the next subsections, I will unpack this definition and discuss the primary components that make up text analysis including research approaches and technical implementation, as well as practical applications.

Aims

Text analysis is a multifaceted research methodology. It can be used to facilitate the qualitative exploration of smaller, human-digestible textual information, but is more often employed quantitatively to bring to the surface patterns and relationships in large samples of textual data that would be otherwise difficult, if not impossible, to identify manually.

The aims of text analysis are as varied as the research questions that can be asked of language data. Some research questions are data-driven, where the researcher is interested in exploring and uncovering patterns and relationships in the data. Other research questions are theory-driven, where the researcher is interested in testing a hypothesis or evaluating a theory. In either case, the researcher is interested in gaining insight from the data.

The relationship(s) of interest in text analysis may be language internal, where the researcher is interested in the patterns and relationships between linguistic features, or language external, where the researcher is interested in the patterns and relationships between linguistic features and some external variable.

Implementation

Text analysis is a branch of data science. As such, it takes advantage of the data science toolbelt to derive insight from data. It is important to note that, while all of the components of the data science toolbelt are present in text analysis, the relative importance of each varies with the stage research. Computing skills being the most important at the data and information stages, statistical knowledge being the most important to derive knowledge, and domain knowledge leading the way towards insight.

Text is a rather raw form of data. It is more often that not unstructured, meaning that it is not organized in a way such that it can be easily analyzed. The collection, organization, and transformation of text data is a key component of text analysis, and computers are well-suited for this task, as we will see in Chapter 2 and Part III “Preparation”.

Once text is transformed to a dataset that can be analyzed, we lean on statistical methods to gain perspective on the relationship(s) of interest. By and large, these methods are the same as those used in other areas of data science. We will provide an overview of these methods in Chapter 3 and do a deeper dive in Part IV “Analysis”.

With the results of the analysis in hand, the researcher must interpret the results and evaluate their significance in disciplinary context. This is where domain knowledge comes to the fore. The researcher must be able to interpret the results in light of the research question and the context in which the data was collected and communicate the value of the results to the broader community. Domain knowledge also plays a vital role in framing the research question and designing the research methodology, as we will see in Chapter 4. Then we will return to the role of domain knowledge in interpreting and communicating the results in Part V “Communication”.

To ensure that the results of text analysis projects are replicable and transparent, programming strategies and documentation play an integral role at each stage of the implementation of a research project. While there are a number of programming languages that can be used for text analysis, R is widely adopted in linguistics research and is the language of choice for this textbook. R, in combination with literate programming and other tools, provides a robust and reproducible workflow for text analysis projects.

Applications

So what are some applications of text analysis? Most applications stem from Computational Linguistic research, often known as Natural Language Processing (NLP) by practitioners. Whether it be using search engines, online translators, submitting your paper to plagiarism detection software, etc., many of the text analysis methods we will cover are at play.

In academia, the use of quantitative text analysis is even more widespread, despite the lack of public fanfare. In linguistics, text analysis research is often falls under Corpus Linguistics (CL). And this approach is applied to a wide range of topics and research questions in both theoretical and applied linguistics fields and subfields, as seen in Examples 1.1 and 1.2.

Example 1.1 Theoretical linguistics

- Hay (2002) use a corpus study to investigate the role of frequency and phonotactics in affix ordering in English.

- Riehemann (2001) explores the extent to which idiomatic expressions (e.g. ‘raise hell’) are lexical or syntactic units.

- Bresnan (2007) investigates the claim that possessed deverbal nouns in English (e.g. ‘the city’s destruction’) are subject to a syntactic constraint that requires the possessor to be affected by the action denoted by the deverbal noun.

Example 1.2 Applied linguistics

- Wulff, Stefanowitsch, & Gries (2007) explore differences between British and American English at the lexico-syntactic level in the into-causative construction (e.g. ‘He tricked me into employing him.’).

- Eisenstein, O’Connor, Smith, & Xing (2012) track the geographic spread of neologisms (e.g. ‘bruh’, ‘af’, ’-__-’) from city to city in the United States using Twitter data collected between 6/2009 and 5/2011.

- Bychkovska & Lee (2017) investigate possible differences between L1-English and L1-Chinese undergraduate students’ use of lexical bundles, multiword sequences which are extended collocations (e.g. ‘as the result of’), in argumentative essays.

- Jaeger & Snider (2007) use a corpus study to investigate the phenomenon of syntactic persistence, the increased tendency for speakers to use a particular syntactic form over an alternate when the syntactic form has been recently processed.

- Voigt et al. (2017) explore potential racial disparities in officer respect in police body camera footage.

- Olohan (2008) investigates the extent to which translated texts imbue more information than source texts through a process known as ‘explicitation’.

So too, text analysis is used in a variety of fields outside of linguistics where insight from language is sought, as seen in Example 1.3.

Example 1.3 Language-related fields

- Kloumann, Danforth, Harris, & Bliss (2012) explore the extent to which languages are positively, neutrally, or negatively biased.

- Mosteller & Wallace (1963) provide a method for solving the authorship debate surrounding The Federalist papers.

- L. G. Conway et al. (2012) investigate whether the established drop in language complexity of rhetoric in election seasons is associated with election outcomes.

These studies in Examples 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3 are just a few illustrations of the contributions of text analysis used as the primary method to gain a deeper understanding of language structure, function, variation, and acquisition.

As a method, however, text analysis can also be used to support other research methods. For example, text analysis can be used to collect data, generate authentic materials, provide linguistic annotation, and generate hypotheses, for either qualitative or quantitative approaches. Together these efforts contribute to a more robust language science by incorporating externally valid language data and materials and support methodological triangulation in language research (Francom, 2022).

In sum, the applications highlighted in this section underscore the versatility of text analysis as a research method. Whether it be in the public sphere or in academia, text analysis methods furnish a set of powerful tools for gaining insight into the nature of language.

Actitivies

The following activities build on your introduction to R and Quarto in the preface. In these activities you will uncover more features offered by Quarto which will enhance your ability to produce comprehensive reproducible research documents. You will apply the capabilities of Quarto in a practical context conveying the objectives and key discoveries from a primary research article.

Summary

In this chapter, I started with some general observations about the difficulty of making sense of a complex world. The standard approach to overcoming inherent human limitations in sense making is science. In the 21st century the toolbelt for doing scientific research and exploration has grown in terms of the amount of data available, the statistical methods for analyzing the data, and the computational power to manage, store, and share the data, methods, and results from quantitative research. The methods and tools for deriving insight from data have made significant inroads in and outside academia, and increasingly figure in the quantitative investigation of language. Text analysis is a particular branch of this enterprise based on observational data from real-world language and is used in a wide variety of fields.